Chi Rho Pages Blue Bejeweled Gospel Cover Art History

The Lindisfarne Gospels, c. 700 (Northumbria), 340 x 250 mm (British Library, Cotton MS Nero D Four) © 2019 British Library, used by permission Speakers: Dr. Kathleen Doyle, Atomic number 82 Curator, Illuminated manuscripts, British Library and Dr. Steven Zucker

A medieval monk takes upward a quill pen, fashioned from a goose plume, and dips information technology into a rich, black ink made from soot. Seated on a wooden chair in the scriptorium of Lindisfarne, an island off the coast of Northumberland in England, he stares hard at the words from a manuscript made in Italia. This volume is his exemplar, the codex (a bound book, made from sheets of newspaper or parchment) from which he is to copy the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

Lindisfarne Gospels, St. Matthew (detail), Second Initial Page, f.29, early 8th century (British Library)

For about the next six years, he will copy this Latin. He will illuminate the gospel text with a weave of fantastic images— snakes that twist themselves into knots or birds, their curvaceous and overlapping forms creating the illusion of a third dimension into which a viewer can lose him or herself in meditative contemplation.

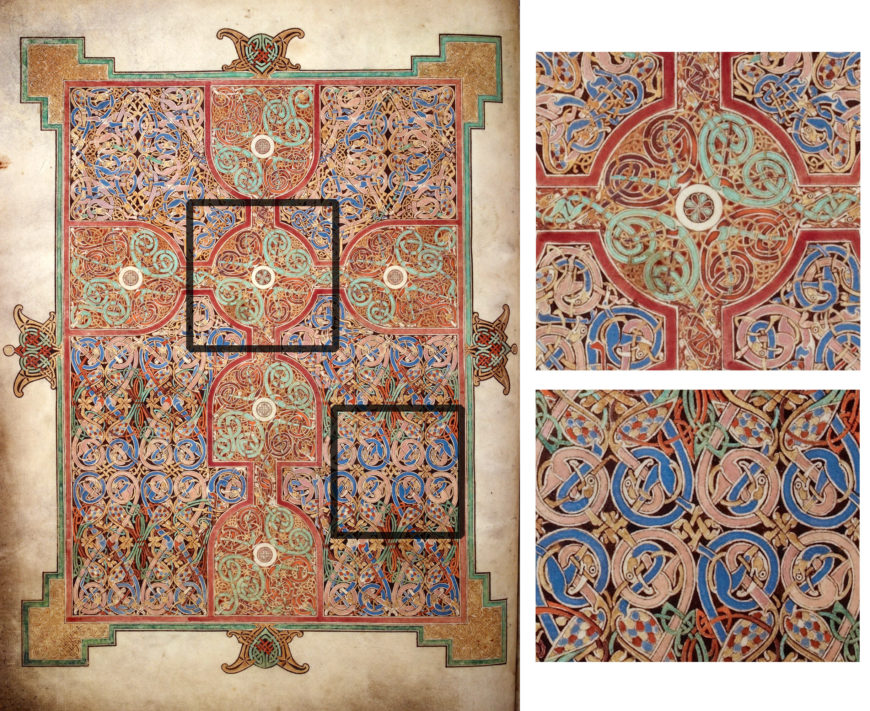

Lindisfarne Gospels, John's cross-rug page, folio 210v. (British Library)

The book is a spectacular example of Insular or Hiberno-Saxon fine art—works produced in the British Isles between 500–900 C.East., a time of devastating invasions and political upheavals. Monks read from it during rituals at their Lindisfarne Priory on Holy Island, a Christian customs that safeguarded the shrine of St Cuthbert, a bishop who died in 687 and whose relics were thought to take curative and miracle-working powers.

A Northumbrian monk, very likely the bishop Eadfrith, illuminated the codex in the early on 8th century. Two-hundred and fifty-nine written and recorded leaves include total-page portraits of each evangelist; highly ornamental "cross-carpet" pages, each of which features a large cross set against a background of ordered and withal teeming decoration; and the Gospels themselves, each introduced by an historiated initial. The codex also includes 16 pages of canon tables set in arcades. Here correlating passages from each evangelist are set side-by-side, enabling a reader to compare narrations.

In 635 C.E. Christian monks from the Scottish isle of Iona built a priory in Lindisfarne. More than than a hundred and l years afterwards, in 793, Vikings from the north attacked and pillaged the monastery, but survivors managed to ship the Gospels safely to Durham, a town on the Northumbrian coast most 75 miles w of its original location.

We glean this data from the manuscript itself, thanks to Aldred, a 10th-century priest from a priory at Durham. Aldred's colophon—an inscription that relays information nigh the volume's production—informs us that Eadfrith, a bishop of Lindisfarne in 698 who died in 721, created the manuscript to honour God and St. Cuthbert. Aldred also inscribed a vernacular translation between the lines of the Latin text, creating the earliest known Gospels written in a form of English.

Lindisfarne Gospels, St Matthew, Cross-Carpet page, f.26v (British Library)

Matthew'due south cross-carpeting page exemplifies Eadfrith's exuberance and genius. A mesmerizing series of repetitive knots and spirals is dominated by a centrally located cross. One tin imagine devout monks losing themselves in the swirls and eddies of color during meditative contemplation of its patterns.

Compositionally, Eadfrith stacked wine-glass shapes horizontally and vertically against his intricate weave of knots. On closer inspection many of these knots reveal themselves as snake-like creatures curling in and effectually tubular forms, mouths clamping down on their bodies. Chameleon-like, their bodies alter colors: sapphire bluish here, verdigris greenish in that location, and sandy gilt in between. The sanctity of the cross, outlined in red with arms outstretched and pressing against the page edges, stabilizes the groundwork's gyrating activity and turns the repetitive free energy into a meditative force.

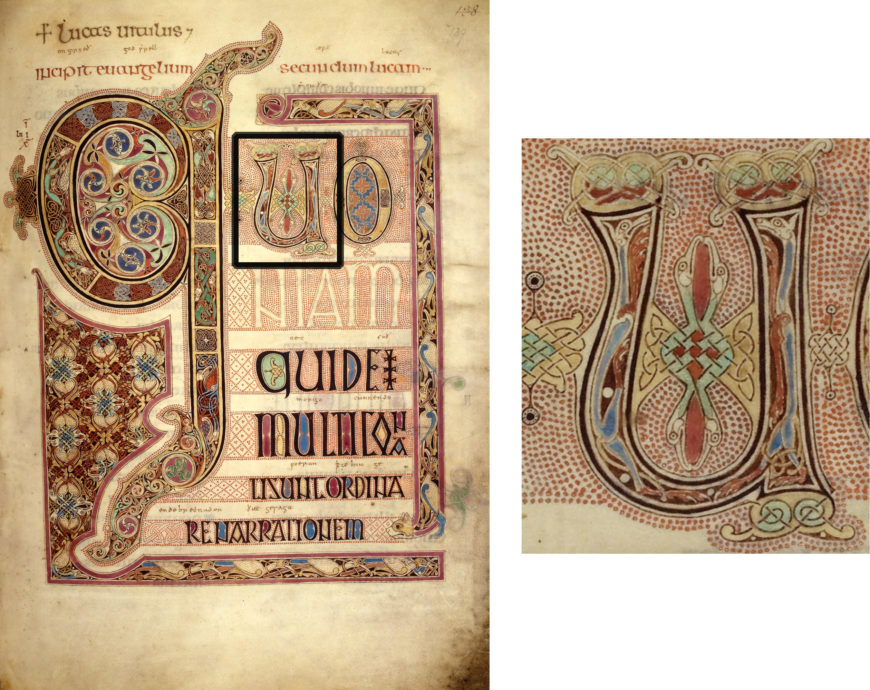

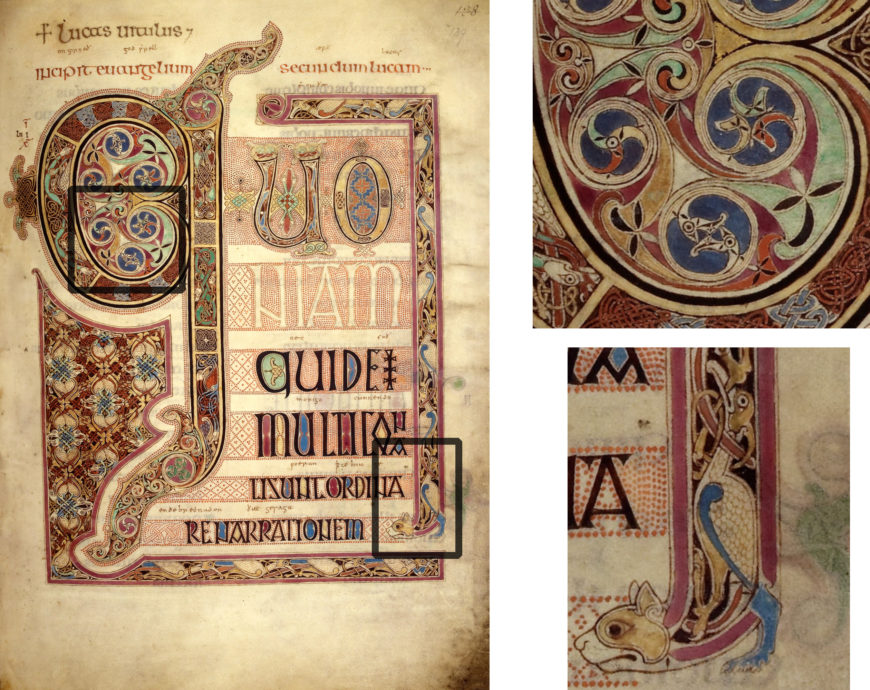

Lindisfarne Gospels, St Luke, incipit folio, f.139 (British Library)

Also, Luke's incipit (incipit: it begins) folio teems with animate being life, spiraled forms, and swirling vortexes. In many cases Eadfrith's characteristic knots reveal themselves as snakes that move stealthily along the confines of a alphabetic character'due south boundaries.

Blueish pin-wheeled shapes rotate in repetitive circles, caught in the vortex of a large Q that forms Luke's opening sentence—Quoniam quidem multi conati sunt ordinare narrationem. (Translation: As many have taken it in hand to set forth in order.)

Lindisfarne Gospels, St Luke, incipit folio, f.139 (British Library)

Birds also abound. One knot enclosed in a tall rectangle on the far right unravels into a blue heron's chest shaped like a large comma. Eadfrith repeats this shape vertically down the column, cleverly twisting the comma into a cat'southward forepaw at the bottom. The feline, who has only consumed the eight birds that stretch vertically up from its head, presses off this appendage acrobatically to plow its torso 90 degrees; it ends up staring at the words RENARRATIONEM (part of the phrase -re narrationem).

Eadfrith also has added a host of tiny red dots that envelop words, except when they don't—the messages "NIAM" of "quoniam" are composed of the vellum itself, the negative space now asserting itself as iv letters.

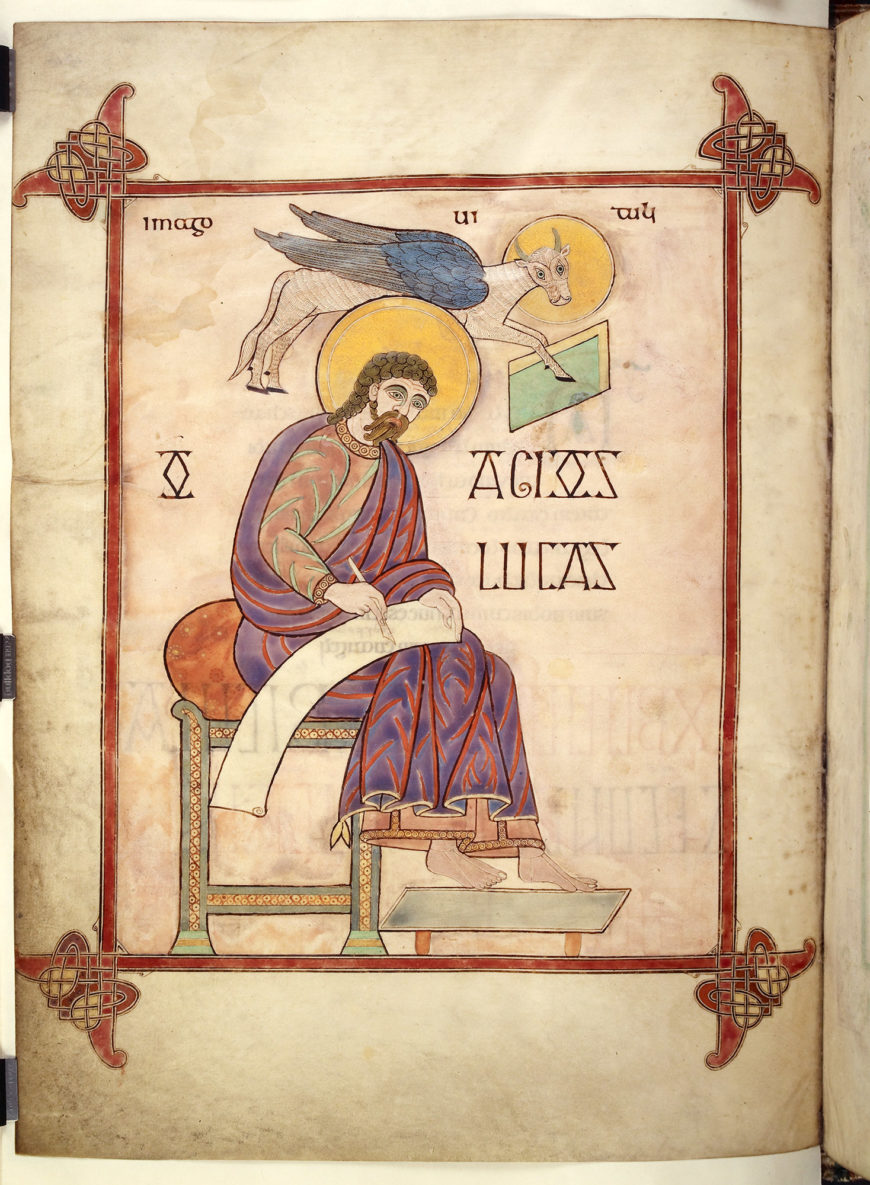

Lindesfarne Gospels, St. Luke, portrait page (137v) (British Library)

Luke's incipit page is in marked contrast to his straightforward portrait page. Hither Eadfrith seats the curly-haired, disguised evangelist on a reddish-cushioned stool against an unornamented background. Luke holds a quill in his correct hand, poised to write words on a curl unfurling from his lap. His feet hover above a tray supported by red legs. He wears a purple robe streaked with red, one that we tin easily imagine on a late 4th or 5th century Roman philosopher. The gilded halo behind Luke's caput indicates his divinity. Above his halo flies a blue-winged calf, its two optics turned toward the viewer with its body in profile. The bovine clasps a green parallelogram between two forelegs, a reference to the Gospel.

According to the historian Bede from the nearby monastery in Monkwearmouth (d. 735), this calf, or ox, symbolizes Christ's sacrifice on the cross. Bede assigns symbols for the other three evangelists besides, which Eadfrith duly includes in their respective portraits: Matthew's is a man, suggesting the human aspect of Christ; Mark'due south the lion, symbolizing the triumphant and divine Christ of the Resurrection; and John'due south the hawkeye, referring to Christ'due south 2d coming.

Lindisfarne Gospels, John's cross-carpeting page, folio 210v. (British Library)

A dense interplay of stacked birds teem underneath the crosses of the carpet page that opens John's Gospel. One bird, situated in the upper left-hand quadrant, has blue-and-pinkish stripes in contrast to others that sport registers of feathers. Stripes had a negative association to the medieval mind, actualization chaotic and disordered. The insane wore stripes, as did prostitutes, criminals, jugglers, sorcerers, and hangmen. Might Eadfrith be warning his viewers that evil lurks hidden in the about unlikely of places? Or was Eadfrith himself practicing humility in avoiding perfection?

All in all, the multifariousness and splendor of the Lindisfarne Gospels are such that even in reproduction, its images astound. Artistic expression and inspired execution make this codex a high bespeak of early medieval art.

Additional resource:

Sacred Texts: the Lindisfarne Gospels at the British Library

Lindisfarne Gospels: an Introduction from the British Library

Lindisfarne Gospels (BBC)

Under the microscope with the Lindisfarne Gospels (British Library Collection Care blog)

Cite this page every bit: Dr. Kathleen Doyle, The British Library and Louisa Woodville, "The Lindisfarne Gospels," in Smarthistory, Baronial 8, 2015, accessed April 27, 2022, https://smarthistory.org/the-lindisfarne-gospels/.

starksmadentopere.blogspot.com

Source: https://smarthistory.org/the-lindisfarne-gospels/

0 Response to "Chi Rho Pages Blue Bejeweled Gospel Cover Art History"

Enregistrer un commentaire